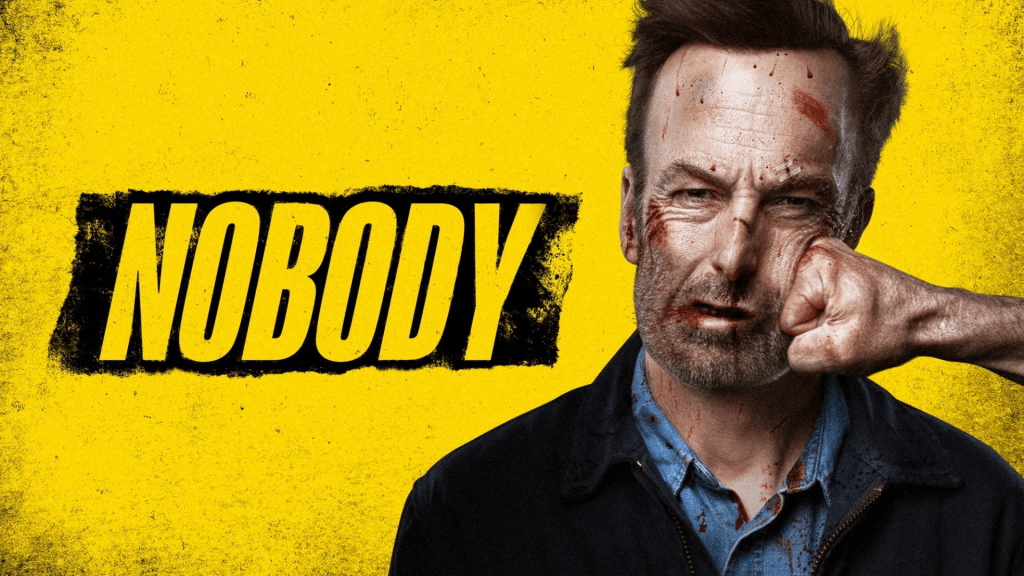

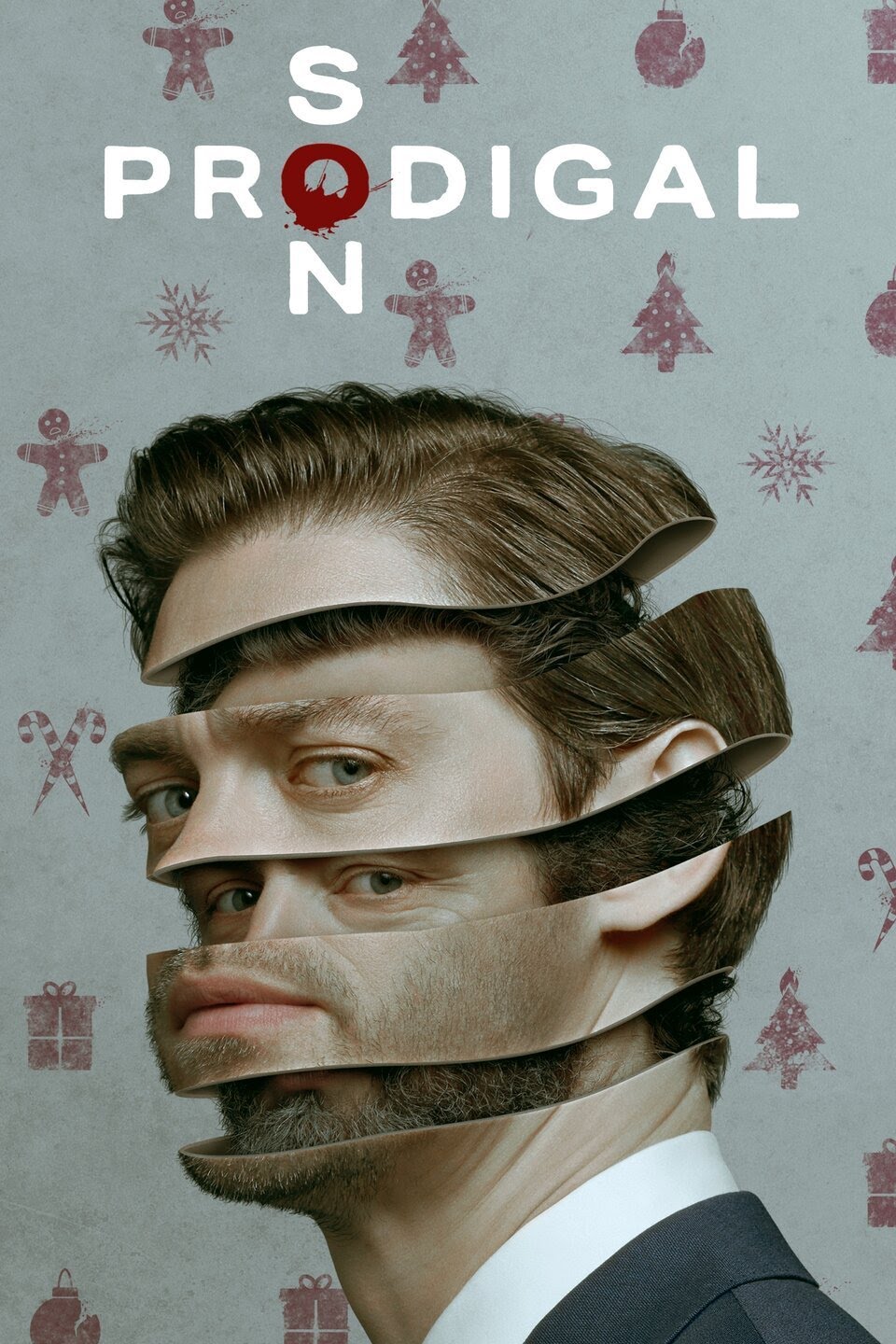

The Beauty of The Prodigal Son

The beauty of The Prodigal Son lies in the complexity and multi-faceted characters cleverly portrayed by an entourage of talented and gifted actors, notwithstanding the writing and directing that goes into each episode. The show is perhaps one of the most intelligent, entertaining, intriguing and multi-complex show of the 2019/2020 season by Fox Television. The show was created by producers and writers, Chris Fedak and Sam Sklaver.

The Prodigal son centers on a young man, Malcolm Bright, whose father, Martin Whitly, is the serial killer nicknamed “The Surgeon”. As a child Malcolm’s curiosity gets the best of him as he is intrigued by his father’s secretive personae. He uncovers a body of a young woman hiding in the basement. But he is caught by his father who uses ether to subdue his son and then later tries to convince him that he was imaging things.

Later a prank call lures a police officer, Gil Arroyo, (played by Lou Diamond Phillips) to the Whitly house to apologize for the crank call. However, Dr. Whitly has other plans for the officer. Young Malcolm warns him that he is in danger of being poison by his dad. At this point Dr. Whitly is arrested, and it is discovered that he is the Surgeon, having murdered 23 women.

Grateful, the police officer thanks Malcolm and gives him a wrapped hard candy. To Malcolm this piece of candy becomes a lifeline. Especially with a man who later becomes more of a father to him than his own father.

Intrigued and shocked at his father’s alternate life of a serial killer, Malcolm decides to become a profiler and join the FBI, much against his father’s wishes. Malcolm becomes obsessed with helping not only the innocent victims but also in trying to show compassion with the killers often risking his own life. At this point in the Pilot Malcolm rescues some victims and comes in contact with the serial killer, who he gets the man to stand down only to be shot by a power-hungry sheriff. Upset Malcolm confronts the sheriff and tells him he killed the man in cold blood to which the sheriff responds he did it to safe him, but Malcolm is not buying and after going back and forth with the officer he punches him. This leads to Malcolm being fired by the FBI.

Back home in New York, he enters his apartment to find his mother waiting for him. Jessica Whitly is a savvy businesswoman from old society money, who copes with the fallout of her marriage to a serial killer and the need to protect her children from that legacy, even after they are all grown, with alcohol and pills. She is often misguided and naïve, which gets her into trouble, but means well. She even goes as far as giving up the love of her life, which we find out by the end of the season to have been and perhaps still is Detective Arroyo, in order to create a healthy relationship between him and her son who desperately needed a father figure. When confronted by Gil, who tells her he could have handled the relationship, she argues back that “No, she was sure she would have screwed that up and Malcolm needed him more.” Wow! Talk about sacrificing everything for your child. Whitly is played by the lovely and talented Bellamy Young, actress and singer, and best known for her role as Mellie Grant in ABC’s Scandal. If you believe that Jessica Whitly, is one sided you are wrong. This character is as complex and multi-faceted as the other players.

It is later revealed that the officer, who Malcolm saves becomes a detective (Detective Arroyo) and a father figured to the boy. The officer, played by Lou Diamond Phillips is forever grateful to the boy for saving his life. The series stars an entourage of actors whose acting talents add to the beauty of this well written and driven drama about a family’s dysfunction that comes from being the product of a serial killer – In this case, Malcolm Whitley’s father, a famed surgeon, known as the Surgeon. A killer of women.

~~~~0~~~~

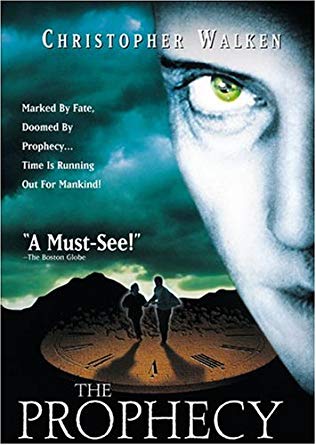

The Beauty of The Prophecy

The beauty of The Prophecy lies in the storytelling of a fictional war between Angels in heaven. The story starts with a narration by Simon, an angel of God, on a mission that will help end Gabriel’s rebellion. Simon tells of a second war being waged in Heaven. The first war being when Lucifer was cast out. The second war, that Simon mentions, is a war waged by Gabriel against God and the other angels over his hatred of Man.

After Simon’s narrative, the next scene introduces the hero, Thomas Dagget (played by Elias Koteas). Thomas is about to take vows to become a priest. He staggers to the altar, almost hesitant. Once he is shown a vision of a war between angels, that causes him to cry in pain and horror, he is dragged away from the altar. “Some people lose their faith because Heaven shows them too little; but how many people lose their faith because Heaven shows them too much” and a verse from St. Paul sticks with him “…even now in heaven there were angels carrying savage weapons.” This line is fictional and not in the bible.

Thomas leaves his faith and becomes a cop. He is special because while his faith was in question he does believe in the battle of the soul between good and evil and therefore a small part of him still believes in God.

At his apartment, he is met by the Angel Simon (played by Eric Stoltz), who sits perched on a chair in Thomas’ room. Thomas has spent his years after the church studying about Angels. Their interaction is quick and ends with Simon asking him “Do you believe you are a part of God’s plan?” and Thomas responds, “It’s a complicated question.” Simon responds, “No it isn’t.”

At his own apartment, another angel arrives to kill Simon. They fight and eventually Simon kills him, but not before he is fatally wounded. Still, Simon proceeds on his mission to recruit the soul of Colonel Hawthorne. A dead soldier who used atrocities during the war and killed hundreds of innocent people. Gabriel is in search of this soldier to help him win the war. So begins a war on Earth for Hawthorne’s soul.

A wounded Simon heads to Chimney Creek, Arizona to acquire the soldier’s soul. He takes the soul but his wounds are fatal and therefore has no choice but to find another host to carry the colonel’s soul. Hiding in an abandoned room at a school, Simon is found by a girl, named Mary (played by Moriah “Shining Dove” Snyder). Simon is pleased to learn the girl’s name is Mary, after all long ago there was another Mary who had given birth to God’s son Jesus. Simon takes her name as a sign. So, he places the colonel’s soul into her.

In the meantime, Mary becomes instantly ill from the burden of carrying such a dark soul. Love the implication here that carrying such darkness in one’s body can affect the body and mind in such a negative way.

Thomas is called to a crime scene where a man was killed by a car and his eyes were plucked out. At the morgue, a hand-written bible is discovered among the man’s belonging. Thomas discovers that the man was the angel Uziel, meaning “Strength of God”, but a lower angel that was Lt. to the Seraph or archangel Gabriel.

Gabriel (played by the amazing Christopher Walken) arrives, and it is soon made obvious to viewers of his hatred for Man: often referring to them as “Talking Monkeys”. He too is in search of the dark soul. After meeting up with Simon, he reveals to him his anger over God placing these talking monkeys over him. He wants to become God’s, only love.

Simon tells him he is not sure who is right or wrong, but that does not matter for in the end we must do what we are told. Simon also tells him he will never tell him what he did with the colonel’s soul. Gabriel then sets Simon on fire, finally killing him.

Upon being called over to the crime scene of Simon’s dead body, Thomas arrives at the school and talks to Catherine about Simon. He asks if any of the children had come in contact with Simon. Catherine admits that Mary was the one and that she was at home sick.

Curious, Thomas researches what was so important about the colonel and discovers that the colonel was guilty of mass killings during his tenure at war.

Thomas heads to the local church. Still in denial of what he knows is happening. He wants to make a connection with God, but instead, is confronted by Gabriel. He soon realizes that he is talking with an angel but doesn’t know it is Gabriel.

When Catherine arrives at the school, she finds Gabriel surrounded by the children. He is looking for souls. A horrified Catherine sends the kids inside. Gabriel turns to the kids and tells them: “Study your Math, it’s the key to the universe.” It is widely believed throughout the scientific community that Math is indeed the key to the universe. But I will leave that for another paper.

When Catherine goes to visit Mary, she finds Thomas there talking to her. Mary then becomes possessed and speaks as the colonel on some of his horrific acts during the war. Thomas tells Catherine about the angels. She then tells him of Gabriel at the school. Catherine offers to help him find Gabriel. She takes him at an abandoned mine. There they see symbols drawn on the rocks. Then an image of the angels dying in the war appears to them.

They race to Mary only to find Gabriel in her room with her. A fight ensues with Catherine getting away with Mary, while Thomas and Gabriel fight. Once outside the camper, Catherine blows up the trailer knocking Gabriel out giving her, Thomas and Mary a chance to escape, but not before Mary tells Thomas that the angels are not immortal. That to kill them you have to cut their hearts out. They head to the reservations where Mary’s people reside. There it is determined that an exorcism is to be performed to rid Mary of the colonel’s soul.

While the group is chanting and getting Mary ready, Catherine heads outside, where she encounter’s Lucifer (played by Viggo Mortensen). The dialogue here is amazing:

Lucifer – “Hello Catherine.”

Catherine – “Oh my God.”

Lucifer – “God? God is Love. I don’t love you.”

Catherine – “Are you one of them?”

Lucifer – “Them?” Catherine – “Are you an angel?”

Lucifer – “I am the first angel, loved once above all others, a perfect love.” He then he sings “But like all true love one day it withered… Gabriel has a plan…and this plan will create two heavens and two hells. “You see I am not here to help your little bitch because I love you or because I care for you. But because two hells is one too many and I can’t have that. What I am offering you here is not only a chance to save Mary but to open Heaven to your kind.”

Catherine tells Thomas about meeting Lucifer. He wonders why God doesn’t talk to him anymore. He tells Catherine that he always had that voice, but the day he needed that voice (God) it left him.

He promises Catherine that he will not let anything happened to Mary. Meanwhile, Gabriel is on his way to the reservation.

The following morning, Lucifer visits Thomas. He taunts Thomas about the many times he heard him pray and was afraid that Lucifer was hiding underneath the bed. “And I was.” He tells Thomas. He then asks Thomas “What is the one thing essential to an angel? The thing that holds his entire being together?” He holds unto to Thomas tightly causing Thomas to react with terror.

Thomas then tells him “His faith.”

Lucifer then asks, “Hey Thomas, what would happen if his faith was tested and an angel just like you didn’t understand. Use that! Use it!” I find it here is Lucifer’s advice to help Thomas with Gabriel, but he also suggests that like Angels, God has also stopped talking to him and that is why he failed as a priest.

Gabriel is now advancing upon the reservation. Thomas and Catherine head back inside where Mary’s exorcism still continues. Once outside, Thomas tells Catherine to head back inside the cabin and lock the door.

Thomas in his fight against Gabriel begins to taunt Gabriel about his faith and finally the jealousy that had consumed him. Why start a war when all he had to do was ask God, but Gabriel tells him that God doesn’t talk to him anymore. Again, the commonality between Man and Angel, that while Man was once revered above Angels, he too faces the same dilemma. So, one can’t help but wonder where was God in all this? Why had he stopped talking to his Angels and Man?

When Gabriel is about to kill Thomas, Lucifer shows up and prevents Gabriel from striking down Thomas. He licks Gabriel’s face. The only reason I could think of for him to do this is to taste and remember what it was like to be an Angel still in favor with God. He then tells Gabriel that his war is arrogance that makes it evil, which then makes it his.

Gabriel asks Lucifer if he is still sitting in the basement sulking over his breakup with the boss.

Time to come home Gabriel, says Lucifer. Killing Gabriel by taking his heart out and eating it. Lucifer then tells Thomas and Catherine to come home with him.

Thomas says no and looks at Catherine to make sure her response is also no. Thomas then asks Lucifer “I have my soul I have my faith What do you have Angel?

Lucifer cannot respond but tells Thomas to leave a light on.

Thomas then narrates “that in the end, it must be about faith and if faith is a choice then it can be lost for a man, an angel or the devil himself and if faith means never completely understanding God’s plan then maybe understanding a part of it, our part is what it is to have a soul and maybe in the end that’s what being human is after all.”

The Prophecy is a 1995 American fantasy horror-thriller film starring Christopher Walken, Elias Koteas, Virginia Madsen, Eric Stoltz, and Viggo Mortensen. It was written and directed by Gregory Widen and is the first motion picture of The Prophecy series including four sequels.

The beauty of it lies in the well-written storytelling, a fantasy world, the acting and directing of the film.

Each character brought the question of faith, pride and rejection to the belief that only Love matters. For Thomas it was his love for God; Catherine her love for Mary; for Lucifer his love of his hell and for Gabriel his love of pride and ultimately rejection that feeds his empty soul with hatred and war.

While people are quick to dismiss this movie, because of the inaccuracies throughout, they forget that some films are meant to distract or pull you in to question faith or belief. The Prophecy definitely pulls one in to ask questions about faith: Why doesn’t God talk to us anymore? Where is God while injustices are going on in the world? But really the important question here is what is your relationship with God? Do you have one? Do you want one? Do you need one?

Like Thomas says it is not about understanding God’s plan, but understanding a part of it, and that part is what it is to have a soul and maybe, in the end, that’s what being human is after all. No matter what God loves us. A film that brings to the forefront such thought-provoking questions or ideas is indeed beautiful. Who’s to say, that through Widen’s story, God is not talking to us?

I hope you enjoy. Please stay tuned as I hope to bring more on the beauties of…

~~~~0~~~~

The Beauty of Nobody

The beauty of Nobody lies in Hutch Mansell’s (Bob Odenkirk) journey, which is defined not by external enemies but by the internal war between his ingrained hitman instincts and his yearning to be a loving husband and father. Introduced as a seemingly ordinary suburban man, Hutch is trapped in the monotony of routine and emotionally estranged from his family, his life drained of meaning.

The film highlights this tension through stark visual and narrative contrasts. Suburban monotony—repetitive routines, strained silences at the dinner table—symbolizes the suffocating cage of domesticity. Hutch’s hidden arsenal and dormant combat skills represent the life he cannot fully abandon, while his awkward attempts at affection with his wife (Connie Nielsen) and children reveal how vulnerability feels foreign compared to the ease of violence. This emotional distance is captured in a quiet moment when Hutch sits at his desk and glances at his sleeping wife, separated from him by a line of pillows—a subtle but powerful symbol of their fractured intimacy and the emotional gulf he cannot cross.

Symbolism deepens this portrayal of internal conflict. The kitty bracelet, for instance, becomes more than a child’s trinket; it symbolizes innocence, the fragile domestic world Hutch desperately wants to protect. His frantic search for it reflects his attempt to reclaim a sense of purpose within family life. Likewise, the suburban home itself functions as a symbolic space: a sanctuary he longs to inhabit fully, yet one that feels increasingly like a stage set for a life he cannot authentically live.

Hutch’s internal conflict intensifies after he attempts to track down the couple who broke into his home. When he discovers that the intruders are impoverished parents caring for a sick infant, he cannot bring himself to unleash his assassin instincts. This restraint leaves him tortured, and on the bus ride home he appears suffocated by the weight of his suppressed identity. Fate intervenes when four intoxicated men crash their car and board the bus, threatening a young female passenger. Hutch whispers, “They say God doesn’t close one door without opening another. Please, God, open that door.” When the men begin harassing the young woman, Hutch seizes the opportunity to release the monster within. The brutal fight that follows is both cathartic and transformative; the next morning, he jogs with renewed vitality. The assassin has resurfaced, and for a moment it seems he may consume the man Hutch is trying to become.

Unbeknownst to Hutch, the group’s leader is the brother of Yulian Kuznetsov, a Russian crime lord responsible for protecting the mob’s obshchak, a communal treasury. Yulian’s pursuit of Hutch escalates the conflict, culminating in attacks on Hutch’s home and his father’s (Christopher Lloyd) assisted living facility. The home—meant to be a sanctuary—becomes a battleground where Hutch’s dual identities collide. This violation becomes the final breaking point. After sending his family away for their safety, Hutch confronts the intruders, confesses the truth about his past, and acknowledges that the charade of normalcy lasted longer than he ever expected.

Here, symbolism again plays a crucial role. Hutch burns the house down, a powerful metaphor for the destruction of the false identity he tried to maintain. The flames consume the illusion of suburban normalcy, leaving only the truth of who he is. Yet before leaving, he rescues a framed picture of his family, symbolizing that while he must shed the lie of domestic perfection, he refuses to abandon the love that anchors him. The picture becomes a bridge between his two selves: the assassin and the father.

Psychologically, Hutch’s struggle reflects the imprint of trauma on identity. Years of killing have rewired his instincts, leaving him hypervigilant, restless, and addicted to adrenaline. Domestic gestures—family dinners, anniversaries, bedtime routines—feel hollow compared to the clarity of combat. His inability to connect with his wife and children underscores how alien vulnerability feels to someone who has survived by suppressing it. Hutch is not merely a man with a violent past; he is a man whose past has become inseparable from his present self.

Philosophically, Nobody resonates with Nietzsche’s concept of the “eternal recurrence.” Hutch cannot escape his violent nature because it recurs endlessly, shaping every attempt at normalcy. His suburban identity becomes a prison, and his relapse into violence after the home invasion demonstrates that denial is futile. Instead, Hutch must confront and affirm his nature. His eventual acceptance—channeling violence to protect rather than destroy—suggests that peace is found not in erasing the past but in transforming it.

Ultimately, Hutch’s struggle arises from the clash between the human longing for meaning and the indifferent chaos of existence. He yearns for the stability of family life, yet his instincts drag him back into violence. Closure is impossible: he cannot be both the gentle father and the assassin. Instead, he finds dignity in embracing the struggle itself. By integrating his violent self into his role as protector, he creates meaning in the face of contradiction.

The beauty of Nobody lies in its refusal to resolve Hutch’s paradox. He is not redeemed by becoming a gentle father, nor condemned to remain only a killer. He exists in the liminal space between, a man who must reconcile love with violence, tenderness with brutality. The film’s action sequences—choreographed with precision and dark humor—become metaphors for this duality: violence as both curse and salvation, destruction as both addiction and protection. In Hutch’s struggle, the audience confronts the universal question of whether we can ever escape the selves we once were, or whether the path to peace lies in embracing the contradictions that make us whole.

The film was written by Derek Kolstad and directed by Ilya Naishuller.

~~~O~~~

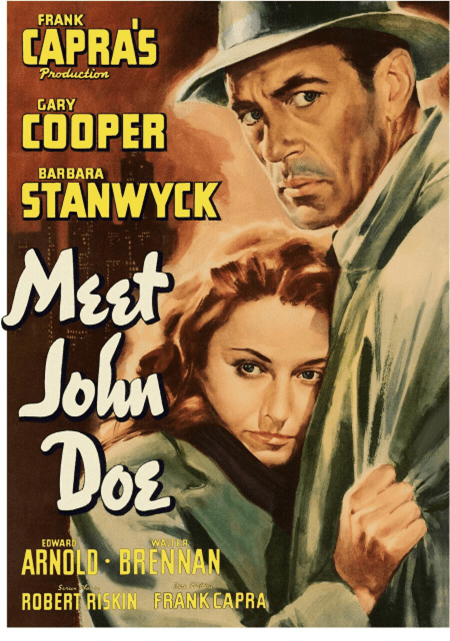

The Beauty of Meet John Doe

The beauty of Meet John Doe lies in the film’s plot which starts with the absence of a man who seems to have slipped through the seams of the world without leaving a trace. Most stories cling to identity as their anchor, but Capra lets go of it entirely. What remains is a silhouette, a question, a wound and in that hollow, the film finds its strange, unsettling power. Recognition becomes the film’s quiet moral demand, a plea for the world to witness the people it routinely erases. To see someone is to grant them a place in the moral universe; to overlook them is to exile them from it. John Doe’s anonymity becomes a wound that exposes the world’s indifference…as you see in the detective who views the John Doe dilemma as a case file; the journalist sees a story and the institutions see a problem to be processed. Unfortunately, for John Doe and others like him, no one sees the man. The film forces us to sit with that discomfort and to feel the weight of a society that only looks up when absence/invisibility becomes impossible to ignore.

Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe is less a character than a gravitational modification. The narrative bends around him the way light bends around a void. Every person who encounters him reveals something they didn’t intend to show. The detective’s weary cynicism leaks through the cracks of his professionalism, while the coroner’s clinical detachment becomes a shield against the discomfort of seeing a human reduced to a case number and finally, the journalist’s hunger for spectacle exposes the machinery of a world that only pays attention when tragedy becomes a headline. The film pretends to search for a man…every man, but what it really uncovers is that society had failed him long before he lost his name.

Cinematic invisibility becomes the film’s theme. The invisibility is not a stylistic flourish; it is a condition of existence. Not only does the world simply fail to see John Doe, because it has forgotten how to look. This failure is not neutral, but ethical. Beneath this ethical surface lies the deeper psychological territory. Invisibility is not just a social condition; it is an internal unraveling of society. The movie hints at the emotional erosion that comes from being overlooked…the way a person can begin to feel transparent, weightless, unanchored. John Doe becomes a vessel for the audience’s own fears: the fear of slipping through the cracks, the fear of being forgotten, the fear that one’s life might not leave a trace. His anonymity becomes a mirror, reflecting the parts of ourselves we rarely confront and the psychological effect of the unseen that extends beyond John Doe. Society’s inability to see John Doe clearly becomes a reflection on its inability to see itself.

Together, these threads form a single, haunting truth: invisibility is not the absence of identity but the presence of a world that refuses to recognize it. The film becomes a quiet indictment of the systems that allow people to fade into the background, unnoticed until their absence becomes a spectacle. John Doe is not a mystery to be solved but a question the film refuses to answer. A reminder that humanity is not measured by the stories we tell about ourselves, but by the attention we give to the lives we overlook. This concept is true even today, as we are experiencing political and social upheavals. In the end, the common man reveals everything precisely because he reveals nothing at all.